Why is it that we can recall events of our wedding day, but we can not remember where we left our car keys?

Feedback is information describing performance in a current activity that is intended to improve future performance in that same or similar activity. Feedback is a widely accepted pedagogical technique across all medical education settings. Models currently exist on how to structure feedback, and were explored in the January 2023 and February 2023 #MedEdPearls. This pearl discusses how emotions influence the feedback process.

Researchers have found that humans are more likely to remember information connected to strong emotions. Medical school and residency are emotional experiences for learners. Emotions modulate individual perceptions and influence how learners perceive, interpret, respond to, make decisions from, and act on information available in learning and clinical practice events. Emotions are affective states that vary along two integrated dimensions: valence (direction: negative to positive) and arousal (strength: neutral to excitatory). Emotion influences motivation to learn and therefore impacts the extent to which feedback will be acted upon.

Emotional arousal of the feedback provider should remain relatively low. Feedback should be given calmly and confidently focusing on facts and observations. Regardless of whether the feedback recipient becomes negatively aroused, the feedback provider must maintain low arousal to display calmness, neutrality, and care to lower the recipient’s negative emotional response and increase openness to the feedback provided.

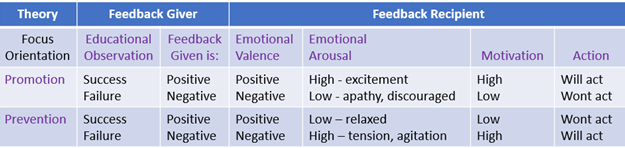

Emotions of the feedback recipient are influenced by self-regulatory focus theory and should be monitored by the feedback giver. This theory describes the recipient’s state of mind during a feedback session as having two orientations: promotion focused or prevention focused. A promotion-focus orientation is identified when the recipient is focused on seeking positive outcomes (e.g. a promotion, reward, or advancement) during the feedback session. Conversely, a prevention-focus orientation is identified when the recipient is focused on avoiding negative outcomes (e.g. loss of job security, privileges) during the feedback session. These two orientations affect the recipient’s emotional response to the feedback received and its impact (See table below).

When the recipient is focused on seeking positive outcomes (promotion-focus orientation), two emotional states are anticipated (Table 1):

o Positive feedback (a success) provided to the recipient stimulates high emotional arousal because he or she is getting his or her needs met within this orientation. This emotional reaction causes high motivation for and engagement with the feedback received, resulting in broadening perspectives, consideration of new strategies, and continued growth.

o Negative feedback (a failure) provided to the recipient often deflates emotional arousal because he or she falsely predicts he or she will not ever obtain his or her desired positive outcome. The feedback provider must provide additional positive emotional arousal through encouragement and clear obtainable expectations to stimulate arousal in the recipient.

When the recipient is focused on avoiding negative outcomes (prevention-focus orientation), two emotional states are anticipated (Table 1):

o Positive feedback (a success) provided lowers the recipient’s emotional arousal as he or she has evaded the feared consequence. This reduces motivation, causing a lack of action to or dismissal of the feedback provided and may lower subsequent performance. To counter, the feedback provider must provide positive emotional arousal through providing new expectations coupled with encouragement.

o Negative feedback (a failure) provided raises the recipient’s emotional arousal (tension, agitation). This causes high motivation to act to avoid future negative consequences, broadening of perspectives, consideration of new strategies for success, and growth.

Table 1: Anticipated emotional arousal of the feedback recipient to feedback valence based on thier regulatory focus orientation.

In conclusion, concerning the feedback recipient’s state of mind (focus orientation), emotional arousal determines the receptivity to feedback and motivation to change to a much larger extent than does the valance of the feedback. Likewise, educators (feedback providers) must be aware of their own emotional states and how their emotions may bias learners’ (feedback recipients) perceptions, interpretations, and actions. Feedback providers can provide new direction and clear expectations with encouragement to activate more positively aroused emotions in recipient, activating reward systems of the brain, enabling consideration of alternatives, and persistence through challenges.

#MedEdPearls are developed monthly by the Health Professions Educator Developers on Educational Affairs. Previously, #MedEdPearls explored topics including counseling and remediating the struggling medical educator, delivering an integrated curriculum, and psychological safety.

Mark Terrell, EdD, is the Assistant Dean of Medical Education, Institutional Director of Professional Development, and Program Directors of the PhD and MS programs in Medical Education at the Lake Erie College of Osteopathic Medicine in Erie, Pennsylvania. His areas professional interests include faculty development, scholarship in teaching and learning in medical education, and cognition and emotion. Mark can be contacted via email.

#MedEdPearls

Jean Bailey, PhD – Virginia Commonwealth University School of Medicine

Rachel Moquin, EdD, MA – Washington University School of Medicine