As the end of the undergraduate medical education school year approaches, medical students study for boards, transition from preclinical to clinical education, attempt to match into residency, and transition into residency as interns. Many will experience stress, setbacks, feelings of burnout and hopelessness, and question why they chose this career. However, research from the fields of positive psychology and the psychology of optimal experience can be combined to help medical educators mentor, coach, and advise struggling students to succeed and flourish during these stressful times by focusing on improving a sense of meaning, control, and optimism.

Flourishing is a transformative concept from positive psychology. In medical and health professions education, the prevalent focus is on diagnosis and treatment, often ignoring the bigger picture of what leads to a truly whole and flourishing life. Flourishing goes beyond happiness to examine a person’s overall well-being, life satisfaction and meaning, and sense of purpose to help them thrive. Flourishing can be measured by recently developed tools.

Flourishing also provides a humanistic lens through which clinical decision making involves major side effects that will impact quality of life, relationships, meaning, and purpose. For example, a young woman tests positive for a genetic variant that greatly increases the risk for breast and ovarian cancers; removal of ovaries would substantially protect her against these cancers but would also make her infertile, thereby potentially compromising her sense of social well-being, purpose, and happiness.

The PERMA model is an acronym for the five building blocks to human flourishing:

- Positive emotions: Experience of positive feelings and emotions, such as satisfaction, awe, joy, and contentment

- Engagement: Being consumed in an activity and environment

- Relationships: Quality and quantity of social connections inside and outside our immediate group

- Meaning: Having a sense of purpose or meaning in life

- Accomplishment: Achievement and progression toward goals

These five building blocks should scaffold our conversations with our stressed and struggling learners. Remind them to stay optimistic to avoid burnout, be fully immersed in what they need to do, avoid social isolation, focus on their greater sense of purpose, and progress toward their short-term and long-term goals.

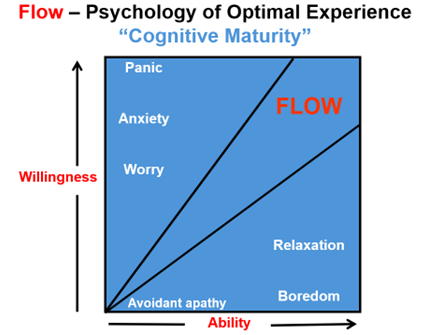

Medical student learning behaviors can be interpreted through the lens of the psychology of optimal experience to determine root causes of learner difficulty. Through an interplay between a learner’s willingness to engage in a challenging task versus their ability, skill, or knowledge to complete the task, quadrants can be identified in the graph below.

Students presenting with high anxiety and panic states may have self-perceived low ability in knowledge or skills when faced with a significant challenge. Conversely, students presenting with apathy may lack ability and engagement. Students presenting with boredom and relaxation have high ability but low willingness to engage in the task. However, when the skill level of the learner is high and is appropriately matched with a task involving a high challenge, then a “Flow State” occurs. During the flow state, a learner is able to:

- Confront a task they know they have a chance at completing

- Concentrate on clearly defined goals

- Provide immediate feedback as to how much they are doing a good job and making progress, such as when they improve a score, receive an applause, or solve a problem

- Feel effortless as they work on the task, allowing one to temporarily forget about the worries and frustrations of everyday life, such as employment, finances, or relationships

- Be in control

- Increase confidence and decrease insecurities, as they stop caring what others thinks as their personal self-worth may come back stronger after the flow experience

- Experience a sense of time that is completely lost

Combining the fields of positive psychology, flourishing, and optimal experience enables medical and health professions educators to help students cope with setbacks. Below are tips that can help educators mentor, coach, and advise struggling students to succeed and flourish. Remind the struggling learner to embrace these behaviors:

- Find the meaning: Setbacks come with an important meaningful purpose and lesson

- Setbacks are temporary: It will not last forever

- Take breaks and treat yourself: Create your own joy

- Learn from setbacks: Do something about it instead of dwelling on it

- Encourage gratitude: It improves happiness

- Stay positive: Recognize that something good can come from a setback

- Tune it out: Limit negativity and remain optimistic

- Accept it: If you cannot change it, let it go

- Just keep going: Life will continue

While learner challenges can be acute at this time of the academic year, building in strategies from positive psychology, optimal experience, and flow into academic mentoring, coaching, and advising practices can foster student flourishing and well-being. This can help students thrive prior to and during times of academic transition.

#MedEdPearls are developed monthly by the Health Professions Educator Developers on Educational Affairs. Previously, #MedEdPearls explored topics including emotion in feedback, performance reviews, and emotionality in teaching and learning.

Mark Terrell, EdD, is the Assistant Dean of Medical Education, Institutional Director of Professional Development, and Program Director of the PhD and MS programs in Medical Education at the Lake Erie College of Osteopathic Medicine. His areas of professional interest include faculty development, scholarship of teaching and learning in medical education, and cognition and emotion. Mark can be contacted via email.

#MedEdPearls

Jean Bailey, PhD – Virginia Commonwealth University School of Medicine

Rachel Moquin, EdD, MA – Washington University School of Medicine