Many medical and health professions educators come from scientific or clinical fields. They may be accustomed to conducting research in their field of primary training, but have not thought about engaging in the scholarship of teaching and learning. It can feel daunting to switch mindsets from clinical, lab, or other scientific research to studying teaching strategies and their effects on student learning. Start small by engaging in an action research project.

What is Action Research?

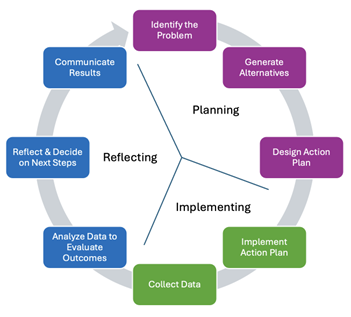

Action research is an iterative, self-reflective, systematic process of inquiry where the aim is to identify a problem of practice in which the educator wants to make data-driven interventional improvements and measure outcomes. This type of research was started in education as a way for teachers to investigate real and relevant issues in their own classrooms, resulting in a more lasting impact on their teaching practice than if outside researchers presented them with recommendations.

There are similarities between action research and quality improvement (QI). Yet, action research is about deliberately intervening in and reflecting on your own practice. This is different from other research approaches, which aim to refrain from changing the research situation and to generalize findings.

The Process of Action Research

Identify the problem: Action research starts with a problem of practice but think about exploring innovative ideas you want to try. How do you generate research ideas?

- Keep a diary to reflect on your classroom or clinical experiences.

- Brainstorm some starter statements below and ask yourself why it is a problem:

- I do not know enough about how my students…

- My students do not like… why is this?

- I would like to find out more about what my students do when they…

- I do not like it when students…

- I get exhausted when doing X with students…

- I feel like X is a waste of time.

- List innovations you would love to try out in your teaching.

Generate alternatives: Search the literature for suggested strategies to address your identified problem. What does the research suggest?

Design and implement the action plan: Decide on an intervention, submit an IRB application, and document your approach..

Collect data: Collect observational and non-observational data.

Observational data:

- Keep a journal with objective facts and reflections. Record how it is working for you and the learners.

- Video or audio record teaching and learning activities and transcribe recordings.

- Ask a colleague to observe and take notes.

Non-observational data:

- Use surveys or questionnaires with closed, ranked, or open questions.

- Conduct interviews, focus groups, or informal discussions with learners, teachers, or colleagues.

- Collect learners’ written texts or recordings of oral presentations.

Analyze your data: You can use various qualitative and quantitative methods. Based on your data, was it effective?

Reflect on your data and decide next steps: Based on what you learned, what will you do next? Should you keep doing it or modify the intervention? Do you want to try with more learners and collect more data?

Communicate results: Share your findings with colleagues. Tell the story of what you did, why, how, and what you learned. It is possible your intervention may only work for you and your context, but it could work for others too. Additionally, sharing your story with others might inspire other educators to do their own action research. Few action research projects exist in health professions education, so your work could contribute meaningfully.

Action research planning guide

- As you begin your project, answer these questions to help you plan:

- What is the problem that sparked your study?

- Why is this problem important to improve your teaching? Answer from your perspective and from the literature.

- What ideas did you get from the literature?

- What changes will you make as a teacher?

- What is your research question?

- How will you collect data to assess effectiveness?

#MedEdPearls are developed monthly by the Health Professions Educator Developers on Educational Affairs. Previously, #MedEdPearls explored similar topics including converting teaching into scholarship, embracing a scholarly approach, and rapid prototyping.

Stacey Pylman, PhD is associate professor of Medical Education and director of Continuing Medical Education in the Office of Medical Education Research and Development at Michigan State University College of Human Medicine. HMI has made an impact on Stacey’s career through an invitation to author and review MedEdPearls blog posts. Stacey’s areas of professional interest include faculty development, effective teaching, and instructional coaching. Stacey can be followed on LinkedIn or contacted via email.

#MedEdPearls

Jean Bailey, PhD – Virginia Commonwealth University School of Medicine

Rachel Moquin, EdD, MA – Washington University School of Medicine