Authors: Jennifer Kasper, MD, MPH; Khin-Kyemon Aung HMS Class of 2019, Chris Murray HMS Class of 2019, Cameron Nutt HMS Class of 2019, Danielle Rabinowitz HMS Class of 2019

Medicine strives to be a healing profession. To heal, we need an understanding of the pathophysiology of disease, but we also need an awareness and understanding of so much more. Why are some people more likely to suffer a triple burden: they are the most likely to be ill, the least likely to have access to diagnostics and therapeutics that would ameliorate disease and suffering as expeditiously as possible, and most likely to suffer the worst outcomes as a consequence of their illness?

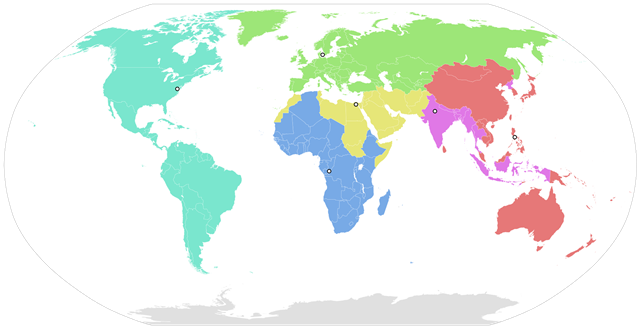

Biomedical explanations cannot explain the health disparities we witness, the unequal burden of disease that some people shoulder. We must explore the factors that reside outside these limited confines. Social medicine is a more expansive approach to studying health and disease in the context of society and medicine. It integrates qualitative (e.g., anthropology, history, political science) and quantitative (e.g., economics, demography, epidemiology) social sciences to understand how micro- and macroscopic social factors influence human disease and its distribution worldwide. Social medicine places individual pathophysiology in a population and societal perspective.

Social medicine recognizes that medicine is inextricably embedded in social contexts. It involves sophisticated questions about the social determinants of disease (e.g. characteristics of where we live, study, work and play), the changing social meanings of disease, the diversity of health care behaviors and practices, and the social factors that influence treatment effectiveness. Any of these factors can transform a seemingly straightforward technical fix into a complicated biosocial problem. A patient’s rich and detailed social history (e.g. language, housing, religious background, immigration status, employment, education) is a window into essential aspects of their health and health care.

Both the Association of American Medical Colleges and the Liaison Committee on Medical Education recommend that the social sciences play a larger role in medical education. Language in the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act states that physicians need to collaborate with community members and organizations (e.g., schools, businesses) outside the traditional clinic setting to address the complex factors that contribute to poor health.

Despite these exhortations, medical school courses on social medicine remain relatively rare. Harvard Medical School (HMS) is an exception. HMS launched a required social medicine course in 2007, and it has been part of the curriculum ever since. This year it was integrated with Health Policy, Ethics, and Clinical Epidemiology and Population Health for an intensive one-month course called “Essentials of the Profession.” The goal of the course is to make social medicine and the other disciplines tangible and applicable to real-world clinical settings. The course teaches that physicians have a responsibility not just to provide care but also to work creatively to achieve desired health outcomes. This tenet is a fundamental reconceptualization of the task—and obligation—of physicians. Technical competence is the minimum that physicians must offer their patients; in addition, they need to do everything possible to improve health outcomes. This requires engaging in their patients’ social worlds.

How can physicians intervene upstream to prevent disease? Once a person is sick and seeks health care, what can be done to harness our knowledge of biological and social forces to improve the delivery of that care and, ultimately, to optimize population health and well-being? A social medicine course, like “Essentials of the Profession,” hones the judgment, analysis, and creativity that students will need to solve these problems.

Another particularly special aspect of the Essentials of the Profession course is the stimulating and provocative conversations that occur among students and faculty. I am honored to teach a remarkable group of medical and dental students. A group of them are working with me on this and future social medicine blogs.

Our patients’ lives are enmeshed in and supported by the intricate scaffolding of family, community, work, the medical system, and a society that stratifies and codifies. The scaffolding may be solid or tenuous, as the following essay from Cameron, Khin, Chris and Danielle will illustrate.

Just a few days after donning our white coats for the very first time in August 2015, we were catapulted into the throes of Foundations, our first science course that introduced us to anatomy, genetics, histology, immunology, cell biology and biochemistry, developmental biology, pharmacology, pathology, cancer, and microbiology. For many of us, the initial few months of medical school were overwhelming. The information overload that we encountered – an experience familiar to all beginning their forays into medicine – could be best described as the attempted act of drinking through a fire hose. We ate, slept, and breathed basic science in those early months, eager to develop the foundational building blocks upon which to later cultivate our clinical knowledge.

Though much of our time was devoted to becoming familiar with the intricate details of biochemical pathways, we had the opportunity each Friday to lift our heads out of the books and learn from our very first patients. Our faculty invited some of their patients grappling with the diseases whose biological underpinnings we had recently studied to meet with us and share their stories. We were granted the privilege of hearing more about the impact of a particular disease process on a patient’s life, allowing us to humanize the science of our classroom work and to raise preliminary questions about the underlying social determinants of health and illness. Here, we heard from a patient with diabetes who actively monitored her electricity bills alongside her hemoglobin A1c levels so that she could afford her many medical copayments; a patient with cystic fibrosis whose greatest fear was not a complication of her illness but rather losing her employer-based health insurance, and the patient with sickle cell disease who encountered racism within the healthcare setting when emergency room clinicians questioned her repeated requests for analgesics in the midst of a pain crisis.

In January, we had the opportunity to delve even further into our investigations through the Essentials of the Profession course, a month-long introduction to the nuts and bolts of taking care not only of patients with diseases, but also of wonderfully complex and unique human beings. It was in this course that we learned about the immense burden of disease in our own communities and the differential access to diagnosis and treatment that our diverse patients face, about how the mortality rate is two times greater in communities like Lowell and Fall River compared to places like Brookline and Newton, and about how differences in rates of chronic diseases are so inextricably and unfortunately tied to factors like geography, income, and race. As aspiring physicians, it was disillusioning at times to realize that for all the cutting-edge treatment modalities and surgical techniques we have in Boston, we, as a profession, far too often fail our patients because of structural biases based on their financial situation, skin color, immigration status, or the neighborhood they call home. The course empowered us with tools and knowledge—including information about the health care system’s design and techniques to advocate for patients— and provided us a framework on which to effectively weave our social responsibility with our clinical commitments.

It has become clear to us that social determinants—income, educational attainment, race, employment status, home and work environments—shape health in fundamental ways. From the gleaming skyscrapers of Back Bay, where life expectancy at birth exceeds nine decades (above that of Switzerland), a five-minute subway journey through the shadows of some of the world’s most well-resourced teaching hospitals leads to Roxbury, where life expectancy is less than 60 years (below that of Iraq or Haiti). In Boston, you are more than twice as likely to develop asthma, diabetes, and depression if you make less than $25,000 per year than if you make more than $50,000 per year. Rates of obesity, hypertension, and preterm birth are significantly higher among those without a high school diploma compared with those who are college educated. Social forces are determining who presents sick to the hospitals and clinics where we train.

It must be our moral and professional responsibility as physicians to not only investigate the pathogenesis of these health disparities, but to also question why outcomes diverge so often once patients enter the health system for diagnosis and care. Who do we allow to fall—or be pushed—through the cracks? White children are more than three times as likely as black children to receive any pain medication for appendicitis upon presentation to emergency departments across the country. Patients with chronic illnesses who face food insecurity or difficulties paying for medications are significantly less likely to be retained in care and more likely to suffer complications including the development of drug resistance or other comorbidities. These disparities do not exist in a vacuum—they persist and widen in our home communities, in our adopted neighborhoods across Boston, and within the places that we train. We must learn to ask and answer questions like, “How do social forces like racism and inequality get into the body?” But as future physicians committed to working together against both disease and injustice, it will also be our charge to ask, “How do we get them out?”

Jennifer Kasper, MD, MPH, received a combined BA/MD with honors from Boston University and Boston University School of Medicine and an MPH from Boston University School of Public Health. Dr. Kasper is a faculty member of the Division of Global Health, Department of Pediatrics at Massachusetts General Hospital for Children; Assistant Professor and Chair of the Faculty Advisory Committee on Global Health at Harvard Medical School; Contributing Instructor of the HMS course, “Essentials of the Profession” and faculty member of the HMS course, “Practice of Medicine;” Pediatrician at MGH Chelsea HealthCare Center; and Presidents’ Council and Board Member of Doctors for Global Health (DGH).

Cameron Nutt is currently a first-year medical student at Harvard Medical School, and also serves as research assistant to Dr. Paul Farmer at Partners In Health. He studied medical anthropology and health policy at Dartmouth College, and has contributed to policy and research efforts related to Ebola, HIV, multidrug-resistant tuberculosis, hepatitis C, and human papillomavirus in Rwanda, Liberia, and Sierra Leone. Cameron hopes to train as an infectious disease specialist.

Danielle Galler Rabinowitz is a first-year medical student at Harvard Medical School. She graduated magna cum laude from Harvard College in 2014 and received a Master's Degree with honors in composition from the New England Conservatory in 2015. Her academic interests include exploring historical intersections between arts and medicine, and she recently served as a research fellow at the Nichols House Museum in Boston, examining the musical and medical pursuits of Dr. Arthur Howard Nichols (1840-1923). As a medical student, Danielle is co-leader of ALL EARS (a medical student-led patient accompaniment program at Beth Israel-Deaconess Hospital), co-president of the History of Medicine Group, and a student leader of the Arts and Humanities Initiative.

Khin-Kyemon Aung is a first-year HMS student and also serves as Managing Editor of Healthcare: The Journal of Delivery Science and Innovation. Previously, Khin worked at the Center for Medicare and Medicaid Innovation where she helped design and implement new accountable care organization models. Follow her on twitter at @khinkyemonaung.

Kasper, Aung, Murray, Nutt, Rabinowitz

Please refer to the blog for Author biographies.