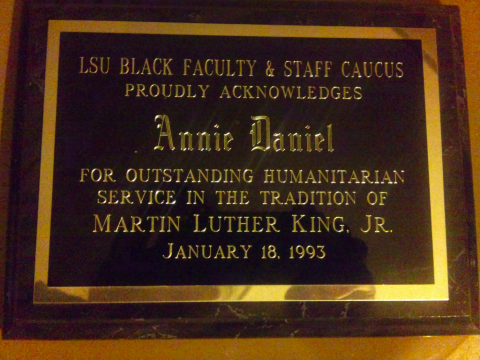

As an undergraduate student at Louisiana State University, I was acknowledged for outstanding humanitarian services in the tradition of Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr., which encouraged me to continue to work towards supporting, motivating and encouraging others to pursue their dreams and careers.

As a graduate student, I enrolled in a required course entitled, “Time Management.” I was a little disturbed at having to take such a course with all of the more important courses I felt I should spend my time completing. However, this course turned out to me the most impactful courses I have ever taken. I thought the course would teach me how to manage my time to be a more effective student and future professional. Additionally, I devoted the semester to reading and applying information about the type of legacy I would leave and how I would impact the people in my life and the world around me. I would spend hours thinking about the different roles I possess, such as a sister, a daughter, a mother, and an aunt.

Our assignments and class discussions were always so rich and reflective. We had to ponder what we want our legacy to be and think strategically how we could accomplish these goals. For many years I grappled with my legacy, until 2014 when I made a career change in order to move back to Louisiana from Iowa where I was employed at the university level as the Director for the Center for Improving Teaching and Learning at Des Moines University. My new position in at the Louisiana State University School of Veterinary Medicine opened up new opportunities for me to work with diversity and inclusion efforts for the School of Veterinary Medicine and the profession as a whole.

I realized that the work I was about to embark upon would be the legacy I had been grappling to find. I created a nonprofit institute, the Institute for Healthcare Education Leadership and Professionals (iHELP) to work with supporting diversity and inclusion efforts in healthcare. The first iHELP initiative is the creation of the National Association for Black Veterinarians (NABV). The purpose of the organization is to work collaboratively with other organizations to support and ensure research-based methods are implemented to increase diversity and inclusion in the veterinary medical profession and in colleges of veterinary medicine. The charter president (Dr. Renita Marshall) and Vice President (Dr. Tyra Brown) were featured in an article that discusses the lack of diversity in the profession which speaks volumes about the need to increase the number of Black people in veterinary medicine.

It was during my research of the profession that my colleagues and I learned the degree and depth of the lack of diversity in veterinary medicine and it is the “whitest” profession in the United States. The number of Black students entering the profession and the number of Black veterinarians in the profession has remained around 2% for decades and in spite of the efforts to diversify the profession, only a few colleges of veterinary medicine have increased the number of Black students enrolling in their programs, therefore the 2% of Black people in the veterinary profession persists. I realized that in order to address this problem those that were being most affected need to come together and collaboratively identify initiatives that are necessary to be in place to increase the number of Black people in veterinary medicine.

As my colleagues and I begin to meet with professionals in the field, students in veterinary colleges, undergraduate pre-veterinary students and professors of pre-veterinary programs in Historically Black Colleges and Universities (HBCUs), we discovered that there are barriers that inhibit entry into the profession. These are the same barriers that our research demonstrated almost ten years ago, which diminish diversity and inclusion from being successful in institutions. Evidence-based practices reveal that there must be strategically planned efforts and resources must be allocated to ensure that the plan can be implemented and successful.

In 2007, the American Association for Veterinary Medical Colleges published a report for improving recruitment, National Recruitment Promotion Plan. This plan details initiatives that should happen from a national perceptive, but there are only a few colleges of veterinary medicine that are using the report as a guide to make changes. The Purdue College of Veterinary Medicine is an excellent example of a school has programs and resources allocated to diversity and inclusion and a robust strategic plan for diversity.

The Liaison Committee on Medical Education - Element 3.3, Diversity/Pipeline Programs and Partnerships for diversity and inclusion is a part of the accreditation standards that require rigorous initiatives that must be in place in order for the medical schools to acquire accreditation. We believe it is this kind of action by the Association of American Veterinary Medical Colleges Council on Education that will move the numbers to increase the number of Black people in the veterinary profession. It has not happened with schools having the autonomy to decide what is needed and what constitutes diversity and inclusion.

In a review of the current and past data, one will see that the numbers have not changed in decades. The number of Black people entering the veterinary profession correlates with the number of Black students being admitted in veterinary schools. If 2% are consistently being admitted and this number does not increase the bottom line will not change. The Journal of Blacks in Higher Education published an article in 1996 that discussed the lack of diversity in the professions and at the time, only had 2% Black people. Now, in 2019, according to the AAVMC Public Data for the veterinary profession, it still only has 2.8 % Black students entering the profession. Our goal is to work as a collaborative group to increase the number of Black people and students learning about the profession, majoring in pre-veterinary studies, and ultimately entering into veterinary schools.

Our research has shown that those students learning about the profession and having opportunities to see people that look like they are more inclined to develop interest and entry the profession. Purdue’s College of Veterinary Medicine has a program that introduces veterinary medicine to elementary students. I recognize that this should happen early on and the experiences should be educational as well as fun, like Purdue’s “This is How We Role” project to increase the awareness of veterinary medicine careers for elementary students.

Additionally, there are several effective research-based efforts that are documented to increase diversity and inclusion, including:

- Outreach: To all educational institutions in the state, inclusive of HBCUs, all public elementary, middle, and high schools , targeting populations of students that may have previously overlooked or thought to be under-qualified.

- Scientifically based Holistic admissions: Holistic review is a university admissions strategy that assesses an applicant's unique experiences alongside traditional measures of academic achievement such as grades and test scores.

- Changing the culture and environment to be more inclusive: Training and improving the knowledge base of all within the institution to acquire an understanding of how inclusion is a key component of diversity and the environment must be assessed to ensure diverse populations are welcome. At the Ohio State University College of Veterinary Medicine, the admissions committee completes an Implicit Association Test (IAT) and Relevant Diversity and Inclusion College of Veterinary Medicine training (e.g. for admissions, search committees), which has shown to lead to a more diverse selection of applicants.

- Setting realistic goals: For diversity and meeting those goals annually.

- Dispelling myths- About the performance levels of underrepresented populations of students’ inability to achieve in a rigorous educational setting.

- Allocating resources: To ensure success for recruiting, academic achievement, scholarships, diverse faculty, staff, and students

- Underrepresented minority faculty: Encounter difficulties in academic medicine that are similar to those confronted by minority students during their medical education.

- Addressing the common barriers: For under-represented minority (URM) students and faculty that includes isolation, stereotyping and/or racism, lack of mentoring, and institutions being inadequately structured for minority faculty advancement.

- Environmental and climate issues: The Association of American Veterinary Medical Colleges-American Veterinary Medical Association (AAVMC-AVMA) reports that underrepresented veterinary students may experience a less welcoming social and academic climate on their campus as a result of overhearing hearing intolerant language, lacking mentors, and experiencing discomfort in less diverse learning environments.

- Addressing the realities of climate issues: These may dissuade URM student trainees from pursuing faculty positions. By determining what institutions can do to nurture minority graduates to pursue to consider entering a career in academic medicine. The AAMC contends that academic health centers can enhance the number of underrepresented minority faculty by 1) creating an environment that allows for a more balanced personal life, 2) supporting community-based initiatives, 3) encouraging interdisciplinary work and 4) rewarding quality teaching efforts. These are recommendations that both veterinary and academic medical health centers should seriously consider developing.

What are your thoughts about increasing diversity in health professions education? Join the conversation by commenting below!

Did you know that the Harvard Macy Institute Community Blog has had more than 210 posts? Previous blog posts have explored topics including health disparities, diversity, and inclusion, cultural competency, and mastering adaptive teaching in the midst of COVID-19.

Annie J. Daniel, PhD

Annie J. Daniel, Ph.D., (Assessment, ‘16) is the Director of Veterinary Instructional Design and Outcomes Assessment in the Office of Student and Academic Affairs in the School of Veterinary Medicine at the Louisiana State University. She earned her Ph.D. in Vocational Education from the Louisiana State University. Her research interests include barriers that prevent Black students from entering medical school, veterinary school and professional and graduate degree programs, effects of mentoring on retention, preparedness, and success of Black students in higher education. Annie can be followed on LinkedIn or Twitter.