As they listen to lectures, work through group learning activities, and study, students may recognize discrepancies in content, flow of material, repetitions, and more. Obtaining student feedback can be very helpful in guiding curriculum design. Students can provide formative feedback to faculty – for example, if a student did not feel that they learned from a particular lecture, they can offers suggestions for how to improve. In turn, faculty can acknowledge student feedback and respond to it, thus closing the feedback loop (as we see in Kern’s 6 Steps to Curriculum Development). If changes were suggested, the faculty member can respond to the class to explain why they could or could not make that change – which students will appreciate!

While feedback is a good starting point, we would like to propose taking it one step (or maybe a few steps) forward: using the student’s experience and expertise to help faculty design the curriculum.

Traditional student feedback mechanisms such as end-of-course evaluations can give a faculty a general idea of what challenges students may have had during the module and create opportunities for improvement. However, in order to make changes to the curriculum that are best suited for student learning, receiving input directly from invested students creates another dimension to the process. It can be particularly useful to have a student who has just completed a course and has recognized that there is room for improvement to contribute their opinion as faculty restructure and reorganize the curriculum. While it is unlikely that major changes in the content itself would occur in a medical curriculum, we can alter the way the material is presented, scheduling, or flow of the course session with student input.

As an example, during part of a summer research project at Eastern Virginia Medical School, we worked on assigning clinical cases from Southern Illinois University School of Medicine to each week of the preclinical curriculum. As a student working through the cases, I was able to determine what seemed relevant to the material we were learning each week. I worked with a faculty member to discuss my choices, and reassigned cases based on our discussion. This showed us how both faculty and students thought through the process, and it helped us make informed decisions about changes in the curriculum.

As part of this project, we wanted to see what students and faculty at our institution thought about students working with the faculty to design the preclinical curriculum. We conducted two focus groups with students and faculty over the summer of 2019. The first part of the focus group was to identify the opportunities and obstacles of the current curriculum at our institution. The second part involved seeking suggestions on how students could help.

The basic conclusion: Student input should be considered in curriculum development!

The common disagreement: How involved should or can students be?

It was not surprising that the faculty and students differed in their opinion about how involved students should be in curriculum design. Students tended to be more willing to become engaged and partner with faculty in the design stages but their concern was time commitment. Alternately, faculty were concerned about administrative deadlines and availability of student time for developing curriculum.

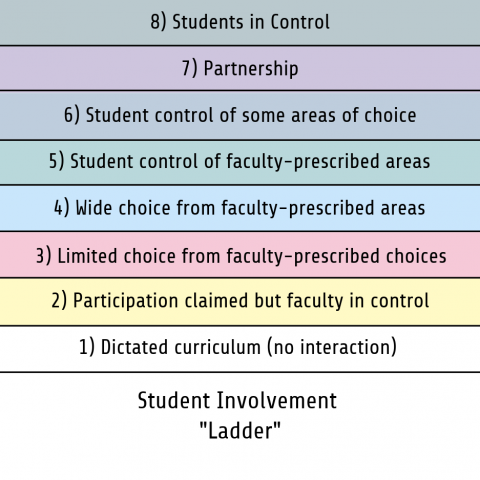

Bovill et al. (2011) elucidated a ‘ladder’ indicating increasing levels of involvement between students and faculty (modified version shown below). As you can see, there are many ways to get students involved, and institutions can work their way up to a partnership. A study by Brooman et al. (2014) demonstrated that student intervention in the curriculum increased not only student attendance to lectures, but also increased performance compared to a faculty intervention. A similar method of practice by Scott et al. (2019) at Harvard Medical School showed positive outcomes with reciprocal feedback and curriculum changes.

One creative solution includes the creation of a “MedEd Club” to involve students at different levels to contribute to curriculum development based on their experiences in the various curricular phases. This also helps to create continuity across the years and offers opportunities for student near-peer mentoring. Another solution is to involve students in the curriculum planning process over the summer prior to the academic year and receive their input as the course is being organized or restructured. This applies a design-thinking method of curricular reform that promotes the learner’s experience. Keeping a record of changes made over the year and their effects is also important to avoid regressing to less helpful methods of teaching.

Overall, students can make a bigger contribution to the curriculum by working with the faculty, compared to prior notions of the educational environment. Who better to add to the team and invest in curriculum than its recipients? How have you engaged students in curriculum design at your institution? Comment below and share your experiences!

Author BIO's

Sarina A. Zahid, M.S. is a second-year medical student at Eastern Virginia Medical School. She is interested in students contributing to medical education, academic medicine, and pediatrics. Sarina can be followed on LinkedIn, Twitter or contacted by email.

Senthil Kumar Rajasekaran, MD, FCP, FAcadMed (Leaders ’13; Assessment ‘14) is a medical educator. Senthil currently holds a position as Senior Associate Dean for Undergraduate Medical Education and Curricular Affairs at Wayne State University, School of Medicine in Detroit, MI. He served as a member of the World Health Organization working group to develop a global competency framework for universal health coverage. Senthil’s areas of professional interest include innovative curriculum design, learner assessment and educational continuous quality improvement. Senthil can be followed on LinkedIn or Twitter, or contacted via email.

Did you know that the Harvard Macy Institute Community Blog has had more than 210 posts? Previous blog posts have explored topics including collaborating with students to build interprofessional opportunities, the case of the missing students, and mastering adaptive teaching in the midst of COVID-19.

HMI Staff