Inclusive Learning

On April 5th, 2019, I had the pleasure of attending a workshop, “Building an Inclusive Classroom,” sponsored by the Vice Provost for Teaching and Learning at Stanford University. The guest speaker was Sherryl Broverman, PhD, from the Duke Global Health Institute and Duke University Department of Biology. Everything that follows is credited to her and represents a tiny glimpse into her outstanding presentation.

The workshop started with the class divided into groups of 5-7 individuals that were given arts and crafts supplies and asked to complete a creative task. When finished, we compared our work between the tables and noticed striking differences. Dr. Broverman set the stage for our discussion by asking, “How do we organize our classrooms so that teaching activities, student performance, and evaluations don’t codify and reinforce existing privilege and social capital?”

Some students did not understand the prompt that described the assigned task.

Some groups were given more supplies than others. They completed more intricate and interesting crafts than groups with less resources.

Some students used their excess supplies without regard for those who were without.

Some groups without resources had students who felt comfortable asking their neighbors to use their excess supplies.

Other students – perhaps first-generation college students, someone remarked – never thought to ask for help at all.

The activity created a polarity in the classroom between those who had resources and those who did not.

Justice in the Classroom

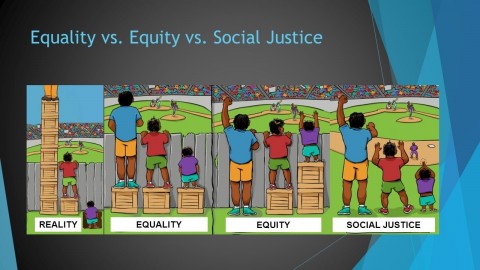

Have you seen the cartoon that illustrates the difference between equality and equity? Several individuals of different heights are straining to watch a baseball game over the outfield fence.

“Interaction Institute for Social Change | Artist: Angus Maguire.” Revised image credit.

“Interaction Institute for Social Change | Artist: Angus Maguire.” Revised image credit.

When we design experiences for equality, everyone gets the same resources – in the cartoon, everyone gets the same wooden crate to stand on. But not everyone has the same starting resources in life… even with the wooden crate to stand on, the shortest individuals still can’t see over the fence.

When we promote equity, we give everyone the resources that they need to reach the same level of achievement. The taller individuals may require fewer crates than the shorter individuals to obtain the same view.

When we seek a just world, we remove any systemic barriers to inequity; in the cartoon example, the fence is torn down.

Dr. Broverman suggested that faculty members tear down the fences in their classrooms in two critical ways:

- Change how we talk and act

- Change how we structure our learning environments

Here are some practical suggestions offered by Dr. Broverman that you might try, some of which she credits to a workshop led by another educator, Kelly Hogan, PhD. For those of you who teach health professions exclusively in the workplace, replace my use of the word ‘classroom’ with ‘operating room,’ ‘clinic,’ ‘simulation center,’ ‘emergency department,’ or the appropriate descriptor of wherever you greet your trainees.

Voice Files

- Record an audio file with the correct pronunciation of your name and provide it to your students

- Encourage students to record audio of how to correctly pronounce their names

- Start your courses without anyone being embarrassed by cultural differences

Pronouns

- Tell your students your pronoun preference (for example, his/hers) and elicit theirs

Small Groups

- Take demographics out of small group assignments

- In classes with only a few women, don’t intentionally put a woman at each table

- Quieter individuals may get talked over due to gender dynamics

- Similar individuals may self-assign themselves to the same table, so they have equal power

- Ask students about their self-assignments if the result feels strange to you

- Reduce the feeling that your student is an ‘only’ or that they don’t belong… it leads to vulnerability

- Sort by experience – who knows how to do what, paired with those who don’t – and ask for peer coaching

- Or simply, randomize assignments

- Build allyship in a group, even though it is difficult

- Set group norms and revisit them throughout the course

Office Hours

- Choose office hours that don’t conflict with other student obligations, such as work-study

- Don’t use a ‘majority rules’ mentality for selecting office hours; this creates a power imbalance and reinforces privilege for some

- Ask for anonymous input on class times to reduce power imbalances

- Consider using online tools such as video conferencing for office hours and record sessions for those who can’t attend

Engaging Quiet Students

- Participation credit can be awarded for student actions other than raising a hand

- Raising hands rewards confidence in some students, reinforcing that they belong in the classroom due to some privilege

- Consider using rotating notecards, Google Docs, or other group work that gives voice to everyone in the classroom -- reducing the fear of judgment associated with raising hands

- Make systematic changes to your classroom that demonstrate value for the introvert, the shy student, and the student whose primary language is not English (and therefore gets mistaken as ‘shy’)

- Distinguish voice in the classroom setting from evidence of student thinking

- Orient your students at the start of a course. Be deliberate in explaining the various ways to participate and demonstrate engagement

- “Participation” credit may not be the best idea in the first semester

- Prepare students for a world that values both individual achievements and teamwork, simultaneously

- Engage students so they gradually begin to increase confidence throughout the semester

Structuring Your Classroom

- Increase active learning in the classroom to reduce achievement gaps between students

- Provide students with ample opportunities to practice new skills

- Add in-classroom problem sets, two-stage quizzes, reading assessments before class begins, optional weekly practice sets, and weekly insight sessions

- Offer more low stakes and formative testing; assessment for learning, not assessment of learning

- Offer fewer high stakes and summative assessments

Getting Started

We must build more inclusive learning environments in the health professions to ensure that our students feel like they belong. Belonging, leading to psychological safety, results in better learning. It can be challenging for many established educators to restructure their classrooms, especially because we may not have seen this style of teaching role modeled when we were students.

Here are two questions that Dr. Broverman offered to close her workshop, which are a great place to start. Reflect on your curriculum design, teaching, and assessment methods:

- Course Design: Who is being left behind?

- Class Environment: Who is not being heard or welcomed?

How have you worked to encourage inclusivity in health professions education? Share your experience below and join the conversation!

Did you know that the Harvard Macy Institute Community Blog has had more than 165 posts? Previous blog posts have explored topics including the F.O.C.U.S.E.D. framework, pedagogy and discharge instructions, and the power of interprofessional education.

Michael A. Gisondi

Michael A. Gisondi, MD is an emergency physician, medical educator, and education researcher who lives in Palo Alto, California. Michael currently holds a position as Associate Professor and Vice Chair of Education in the Department of Emergency Medicine at Stanford University. You can contact Michael by visiting his website or following him on Twitter.